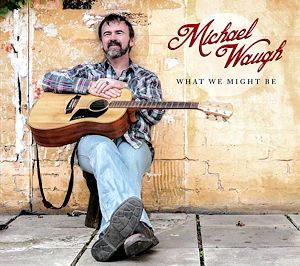

DAVE'S DIARY - 1 FEBRUARY 2016 - MICHAEL WAUGH CD REVIEW

2016 CD REVIEW

MICHAEL WAUGH

WHAT WE MIGHT BE (MGM)

FRIESIANS, JERSEYS , TEACHING AND SINGING

“On summer nights we listened to his wheezing/ the asthma never gave him any rest/ each hay-carting season, he struggled with his breathing/ as if the farm was sitting on his chest/ I didn't sleep those nights when I was young/ I was raised a dairy farmer's son/ the hayrides look romantic in the movies/ they don't show how the thistles scratch your arms and hands/ there's no pretty cowgirls on the tractor/ just dad and sunburnt brothers picking grass seeds from their sweaty underpants.” - Dairy Farmer's Son - Michael Waugh.

|

Dairying has a rich history in Australian country music from late bush balladeer Slim Dusty's bovine roots near Kempsey on the northern NSW coast and Reg Poole and John Williams in the Goulburn Valley of Victoria.

But, now Latrobe Valley raised dairy farmer's son and latter day teacher-singer-songwriter Michael Waugh, has personalised the noble agrarian culture in a far more accessible mode on debut album What Might Be.

Not only has Waugh graphically depicted his family struggles and roots of his rural raising he has also captured childhood and adolescent memories of growing up way beyond the neon in a valley where demise of coal and other industries have destroyed small towns.

So let's soak up memories turned into melodic melancholia by an artist who has the dual benefit of being raised on dairy farms before teaching and raising children in the big smoke of inner suburban Melbourne .

Waugh vividly recalls 5 am work day starts of dairy farmers - with and without irrigation - on his family farms near Maffra and Newry in East Gippsland.

This is not new age hi-tech agriculture on multi-national corporate dairy farm factories with thrice daily and round the clock milking sessions now threatening livelihoods of family farmers.

Waugh vividly recalls the nocturnal asthmatic wheezing of his dairy farmer dad in an era before masks were worn by farmers, hay carters and others exposed to the hazards of harvest irritants.

“It was the sound of my father struggling under the weight of asthma, a massive mortgage and a workload that would never end,” Waugh explained.

Sadly hindsight was not the strong suit for sons and daughters of the soil who toiled in parched paddocks dating back to the 19 th century.

I can empathise with Waugh, now 45.

I watched my dairy farmer dad hooked up to an oxygen mask for his final five years in his Hopkins river bank home near Warrnambool on the Victorian Shipwreck Coast after the city specialist diagnosed it was the pollen in the hay that finally claimed his lungs in his sixties.

It was a slow painful death that he urged his children to avoid at all costs - my sister, like Michael Waugh, chose teaching and this son of a son of a dairy farmer fled to Van Diemen's Land and way beyond to pursue a 50 year career in journalism, radio and TV.

My sire was a supreme athlete - 1927 APS 800 metres champion - and country footballer in his youth and adulthood before working as a jackeroo and agricultural consultant in the outback and returning to the family farm and enlisting as a Captain in the Army during World War 11.

It was where he met my Laharum farm raised mother when she drove a troop carrier in the same not so distant war.

That may seem like too much personal info but let's move on from Waugh's Dairy Farmer's Son to album entree Heyfield Girl.

HEYFIELD GIRL - WAUGH MATRIARCH

“They don't write pretty love songs for girls born in Heyfield/ American women get songs about how they're adored/ Tennessee girls get to waltz, Californian girls they've got no faults/ but they don't write love songs about girls from Heyfield at all/ no they don't write love songs about girls from Heyfield at all/ my dad loved my mum with affection familiar/ and long as an old country road/ but there's not a melody written to sing of/ the depths of the love that they've known/ so even when cancer took part of mum's body/ and the chemo took all of her hair/ Dad used to tease mum about girls from Heyfield/ cause that's how she knows that he cares.” - Heyfield Girl - Michael Waugh.

|

Waugh's father John met his mother Eileen in nearby timber town Heyfield he singer recreated their romance in Heyfield Girl. The town may be a mystery to city slickers but I have vivid memories of it as I spent nine years at boarding school with a boy whose name was butt of cruel jibes as his dad Dr John Graves was the local medico in Heyfield. Waugh injected his song with maternal and paternal passion from an era when writers eulogised sweethearts of the rodeo and radio from towns and cities in the home of country music - Tennessee , Texas , Kentucky and the Appalachians. |

He also illustrated his love song with memories of the childhood car trips of the family - parents and three sons - listening to country music on the Gippsland highways and back roads.

It's a familiar soundtrack for rural family journeys in an era when the hits were heartfelt homilies penned and/or sung by artists diverse as Glenn Campbell, Patsy Cline, Dolly Parton, Jim Reeves, Johnny Cash, Waylon and Willie and Kenny Rogers.

Not the current radio fodder mass manufactured by song-writing committees milking fads of the day.

Or worse still the lyrically challenged chumps of pop, rock, rap and techno.

Many bush balladeers sang of our country towns and the outback in that era.

But they didn't have the vocal access of nouveau home-grown local writers like Waugh and mainstream peers Troy Cassar-Daley, Adam Harvey, Catherine Britt, the Kernaghan and Chambers clans, Shane Howard and producer Shane Nicholson.

Ironically, after a 10 year performing hiatus, a momentous event inspired Waugh to return in 2012.

He wrote Heyfield Girl about his mother's battle with cancer and dug a little deeper by singing of his father's tongue-in-cheek teasing of his story telling mum because she hailed from the timber town.

Waugh humanised the struggles of his mother from ravages of a different cancer that claimed his father's health at a younger age.

It won gongs at Maldon Folk Festival , Canberra and Tamworth and was title track of one of his two EPS released in 2013.

Heyfield Girl and his Drafts EP took him to the 2014 Port Fairy Folk Festival where he met and performed with ARIA award winner Shane Nicholson who produced this album.

“My musical education was in the back seat of a Ford, driving down bumpy tracks on long country drives,” Waugh recalled of the sonic roots of Heyfield Girl .

“My parents played car tapes - usually Greatest Hits collections of American Country singers - and you had no choice but to look out the window and listen to the stories. It was a case of learn to love country music or jump out of the moving vehicle.

Those American songs seemed larger than the little country life that I was living. But they were also the closest thing we had to the soundtrack of growing up in East Gippsland . In this collection of songs I wanted to create stories like those musicians and songwriters who are my heroes. The texture of their rhyme and meter is the shacks and bars and snowdrifts of American life. I wanted to capture the magpies and lawnmowers and footy games of rural Australian life. Because, to me, that is the beauty and the poetry of how I grew up. Maffra, Heyfield and Sale may not have exotic twang of Nashville - but we've got the Macalister Hotel, Mafeking Hill, Heyfield Timber Mills and more cows than you would ever want to have to get up at 5am to milk. And there's music in our stories, too.”

Waugh's family and rural roots were a major impetus for many songs including the equally evocative My Dad's Shoes - a masterful metaphor for a boy whose dad was disciplined by his mum for wearing manure splattered Blundstone dairy boots in the family home.

The Waugh patriarch may have had to sell the tractor and farm when age and mortgage decimated his health and wealth but those boots march on.

Waugh expands on the title to illustrate the pride of following in his father's footsteps, aka Blundstone's, to aspire to raising and providing for a family of his own by digging his heels in.

HEART OF THE VALLEY

“There's a hole in the heart of the valley where they dug out all the coal from the seam/ and a freeway cuts around what used to be the town/ in a time before they sold the SEC/ they left a hole where Morwell's heart used to be/ the Morwell River used to feed the people of the Kurnai/ before we bulldozed them away/ now some teenaged boys are drinking goon and tagging closed up stores/ like stray dogs pissing on a wall.” - Heart Of The Valley - Michael Waugh.

|

Waugh also excels in social comment on the demise of Latrobe Valley coal towns after their heart and soul were decimated when they were mined out and the highway by-passed their commercial centres. It's a familiar story in many once rich mining and rural towns but Waugh has the benefit of living there in the halcyon days and observing their current plight. “They are little country towns with their guts ripped out of them as industry and infrastructure were stripped away,” Waugh says. Recent events have accentuated those socio-economic problems so Heart Of The Valley now resonates even more. |

Waugh also explores pit-stops in life's eternal cycles.

He recalls blissful weekends in Mafeking Hill in Maffra .

It's a tale relevant to country towns throughout the nation in an era when shops closed shortly after high noon, leaving young boys and girls to follow their day dreams on bikes, billycarts and other modes of transport.

It's a vast contrast to Paul where he explores the cruelty and bullying suffered by peers - a familiar saga of boys deemed to be misfits in a country town.

Waugh details vicious torture of little boys in change rooms, humiliated because they were weird or gay or too original for their pubescent peers.

This pungent parable finds the victim, suffering jibes because of his obesity and perceived homosexuality, arming himself with a shotgun to deliver summary justice to his tormentors.

Waugh also evokes compassion in his tribute to a younger sibling he nurtured and protected in the nostalgia laced Brother.

Equally evocative is the personal This Will Pass - an ode to his young son as he grows up and follows in his dad's footsteps.

But it's Find You - a pathos primed paean about Alzheimer's - that graphically depicts ultimate sadness of grandparents who have been married more than 40 years and retired from their farm.

They go through their retirement rituals that become a blur one Christmas when their collective memories fail and they can't recognise each other.

It's a fast growing not so hidden illness that is mushrooming in our ageing society.

“The old men who slaved on farms for years and then slipped into forgetting, as Alzheimer's stole the peace that they worked their whole lives to enjoy,” is Waugh's explanation.

TERRORISTS AND PLANES

“Kids home after school playing terrorists and planes/ no one seems to worry about the violence of their games/ they're laughing as they get shot down while bursting into flames/ kids home after school playing terrorists and planes/ young skateboard rider shot down at All Nation's Park / holding his fists in rage with a kitchen knife from K-Mart/ Northcote Plaza's not the Gaza but it isn't a world apart/ police shooting fifteen year olds with fear inside their hearts.” - Terrorists And Planes - Michael Waugh.

But Waugh doesn't confine his observations to the bush.

As a secondary teacher in the big smoke he has been exposed to perils of a new generation raised on violent computer games where reality and fantasy have become a hybrid - dangerous and contagious killers.

Unlike the writer's farming and sporting youth there's few safety valves for teenagers now raised in an era where the nightly news is a staple diet of doom and destruction.

Waugh bases Terrorists And Planes on a recent tragic true life saga that claimed the life of a boy named Tyler , just 15, in a Northcote skate park.

The well documented fatal incident involved the boy stealing a knife from a Northcote Plaza K-Mart and committing suicide by cop in the local skate park.

Sadly, the current climate of fear from the threats of teenage terrorism has made the mean streets even meaner - especially in suburbs like Northcote where Nu Country FM once broadcast before its studios burned down on June 26, 2000.

The Beer Can Hill radio station was resurrected in 2001 at the Paris , Texas , end of Collins St but there were no reprieve for Tyler and his grief stricken mum whose most pertinent epitaph may be Waugh's devastatingly accurate Terrorists And Planes .

It was a vast contrast to Waugh's childhood.

He graduated dux of Maffra High School in 1988 and performed in school plays and musicals, the Sale and Maffra Dramatic Societies and won awards for singing at local eisteddfods, including Yarram where he debuted his song-writing.

Michael also studied drama at Deakin University and singing at the Melba Conservatorium .

He worked in folk trio, St Vitus , releasing a record Motor Mouth through Black Market Music, won Song of Peace, Tolerance and Understanding at Port Fairy Folk Festival and Australian Songwriters Association Rudy Brandsma Award for excellence in song-writing.

Irish-Australian folk singer, Enda Kenny, covered Michael's song New Releases on his Cloudlining album.

But as a young father, Michael gave up singing and song-writing to focus on his career as secondary school teacher.

He completed his Honours Degree in Literature, Post Graduate Diploma in Student Welfare and Masters in Education.

FOOTY ON MUDDY DAIRY PADDOCKS

“They're all brutal men/ when Sale Catholic College versus Maffra Under 10s/ the cows all low in sympathy when the final siren screams/ and it's blown by someone's mum from a car parked near the canteen/ and the scoreboard's final tally is College 7 points to 8/ and the winning point to Maffra kicked by College by mistake.” - Maffra Under 10's - Michael Waugh.

|

Living on the mean streets of Northcote in a later era precluded previous song subject Tyler from enjoying the athletic pursuits and longevity of the youngsters in this album's footy fable finale Maffra Under 10's.

Waugh recreates rural rituals where boys and girls dream of sporting stardom as they play football on muddy fields near dairy paddocks where Friesians and Jerseys roam before and after milking.

The singer personalises the not so trivial pursuits of young footballers by setting the battlefield between Sale Catholic College and Maffra Under 10's .

It's here the pre-teen combatants compete in front of cars parked behind the oval fences where car horns are often mistaken for sirens that start and end each quarter and game.

Waugh name checks footy icons including Drouin raised Gary Ablett, Kevin Sheedy, Alex Jesaulenko, Buddy Franklin and Nick Riewoldt in the song that finds the combatants hoping to reach the under 14's before soaring even higher.

The punch-line is the winning score - a point kicked by mistake by the opposition team.

A fitting finale by Waugh whose family name may seem more suited to cricket.

“I wanted to give voice to all of these stories, because they are about brave, beautiful, honest, undervalued and overworked men and women who taught me what to be,” Waugh says of his eclectic album that may seem like a sleeper but is destined to win acclaim and awards way beyond the mainstream.

“I'm honoured to have come from Gippsland and to be a dairy farmer's son. My mum is a great storyteller. My dad is a dairy farmer. They are about as ordinary as you can get but they are the bravest and strongest people that I know. I'm at a place now where I can recognise how incredible their story is. When I was growing up, it was just life.

“As I fumble my way through adulthood and fatherhood, a backwards glance gives me insight. And I'm proud that I come from there - even if I don't always know where I'm heading to. As I said in the dedication on the record sleeve - they supported me to be what I was and my family in Melbourne give me hope for what we might be.”

A hard act to follow.